“I meant it like this, follow the plan,”

“Thanks, that sounds good. I’ll try it another way.”

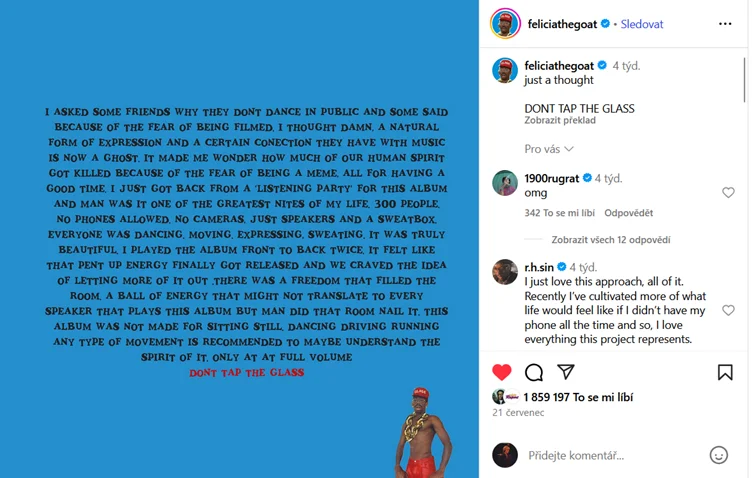

In July, during his world tour, Tyler, The Creator surprised his listeners without much prior teasing by releasing a new album, DON’T TAP THE GLASS. While listening to his latest work, we are supposed to move. This essay reflects on whether we truly have to, and to what extent it remains within the authority and power of the creator to oversee what his work is and how it will be perceived.

Representatives of the American literary school New Criticism, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe C. Beardsley, rejected the idea that criticism should concern itself with assessing the author’s intention. They insisted that works should instead be stripped of any surrounding context.

“We claimed back then that as a criterion for evaluating the success of a literary work of art, the author’s intention or purpose is neither valid nor desirable…” ¹

For the construction of the argument in this essay, I will mention two of the five axioms proposed by Wimsatt and Beardsley, which should discourage us from searching for the author’s intention. Whatever the artistic work is meant to be during the process of creation, this does not mean it will be the same as what the perceiver encounters in the finished work, even though it cannot be denied that the processes of creation and reception are mutually connected. Artistic works should therefore be judged like machines or puddings, based on whether they function and taste good. ² The only thing that should be relevant for us is what we find within the work itself. Wimsatt and Beardsley call this the internal evidence, which concerns how the artistic work is written and structured; in literature, we access this evidence through language, while external evidence includes what no longer belongs to the poem itself—under what conditions it was written, why the author was creating ³, and all the other circumstances that were so important for Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. ⁴

From the perspective of New Criticism, the information that the new album by The Clipse was created with Pharell Williams at headquarters of Louis Vuitton ⁵ should be entirely irrelevant to us. Either we hear refinement, exclusivity, and luxury in their rap, or we will never hear these attributes there, because they cannot be added afterwards based on supplementary external information (the author of the essay considers Let God Sort Dem Out a refined, exclusive, and luxurious work). New Criticism does not care what the creators tell us about the environment and atmosphere in which an artistic work came into being. For them, the work either functions or it does not.

True to the spirit of New Criticism, I approached DON’T TAP THE GLASS with no prior context, allowing the text to speak for itself. An unmediated listening, uncorrected by anything or anyone, left me with initial ambiguous impressions of lack of substance. I do not mean to suggest, by any means, that this experience is similar to the kind of outrage experienced by Nietzsche’s Zarathustra.

“And once did I want to dance as I had never yet danced: beyond all heavens did I want to dance. Then did you seduce my favorite minstrel. And now has he struck up an awful, melancholy air; alas, he tooted as a mournful horn to my ear! Murderous minstrel, instrument of evil, most innocent instrument! Already did I stand prepared for the best dance: then did you slay my rapture with your tones! Only in the dance do I know how to speak the parable of the highest things:- and now has my grandest parable remained unspoken in my limbs! Unspoken and unrealized has my highest hope remained! And there have perished for me all the visions and consolations of my youth!” ⁶.

Yet I cannot deny a certain immediate, slight disappointment, especially from the perspective from which Tyler describes all his artistic works as insights into where he happened to be at the time.

“It might have been Baltimore or Detroit or something, but I was like, ‘Man, I’m so lucky that… ‘I was going through the records, and I was like, ‘Yooo, it’s sick that I get to stamp moments of my life on these albums where I am at, and you all get to enjoy these things with me and go through the records.‘ I get to look back and be like, ‘Oh, that was that version of me; that’s super sweet. And I was telling them, like, ‘Man, whoever is out there making music, please, whoever you are at the moment, put that shit at 100% even if folks ain’t fucking with it.‘ Because some folks don’t like Call Me If You Get Lost Tyler. And that’s ok. I love that they don’t. But that is where I was right then… And it’s beautiful sitting next to Goblin, and it is going to be beautiful next to whatever I’ll put out at fifty. Cause it is just real life. Not just the lyrics, but the sounds and the tempos…” ⁷

In the expectation of another vulnerable and honest deep dive into where Tyler currently finds himself on his journey, I felt that something was missing on DON’T TAP THE GLASS. According to the American philosopher Kendall L. Walton, it was the context and the choice of an adequate way to perceive Tyler’s new work.

“For this reason, and for another as well, the view that works of art should be judged simply by what can be perceived in them is seriously misleading, though there is something right in the idea that what matters aesthetically about a painting or a sonata is just how it looks or sounds.” ⁸

Kendall L. Walton suggests that there are several fairly clear criteria for achieving the right way of perceiving a given work. We should choose for ourselves such a category of perception in which there will be a minimum of nonstandard features. Furthermore, we are to perceive the artistic work in the way in which this creation stands best. We should take into account the artist’s expectations of how the work will be perceived and finally work with how the work would have been perceived by the artist’s contemporaries. ⁹ For finding the correct mode of perception, historical conditions—namely the artist’s assumptions and intentions together with the views of contemporaries—are of key importance. ¹⁰

My unprepared approach to DON’T TAP THE GLASS would be, for Kendall L. Walton, a mistaken one.

“If a work’s aesthetic properties are those that are to be found in it when it is perceived correctly, and the correct way to perceive it is determined partly by historical facts about the artist’s intention and/or his society, no examination of the work itself, however thorough, will by itself reveal those properties.“ ¹¹

I therefore decided to read Tyler’s manifesto.

I also listened to an interview where Tyler described his creative process, thereby framing DON’T TAP THE GLASS with a context that completely transformed my perspective.

“You know what? I want to be silly again. I just want to have the inside jokes and the fun dumb shit me and my friends was laughing at. I ain’t going to write about no deep shit. I don’t want no album cuts.” ¹²

“I recorded it all on tour in May while I was in Europe. And I said, ‘You know what? Imma finish this, and as soon as I’m done, I’m uploading it. I don’t want to do no press, I don’t want to do no interviews, and I don’t want to do nothing.‘ I’m just uploading it because, dude, I did the fucking big rollouts. I got the awards. I got the number ones. I got that, bro. I just want to just make some cool shit to me and just put this shit out. No more being precious, bro. Like I did the precious shit. The long intros, the outros, the bridges, and the beat switches.“¹³

Suddenly, I began to perceive DON’T TAP THE GLASS as an immensely fun, playful, and vivid creative gesture. “That creative rush I had. I had to put it out. With that terrible Photoshop cover, which I love, because that’s my roots. It’s out and it’s cool. Summer shit. Bam.” ¹⁴ I realized that my first listen had not been as genuinely unbiased as I thought. I approached DON’T TAP THE GLASS in the context of the themes Tyler dealt with on Chromakopia, which from Walton’s perspective would not be the right way of perceiving it, since it didn’t allow the new Tyler album to stand out in its best possible light. “I just wanted to have fun again. On the last album I was dealing with abortions. I wanted to be wild again. I wanted to be goofy. I hope I never lose that.” ¹⁵

he unrestrained immediacy and carefreeness inherent in the act of releasing DON’T TAP THE GLASS shine a provocative light on the almost obligatory promotional campaigns that now accompany any creative or non-creative project.

“On Saturday I said I’d release the album Monday morning. And I just released it. You can do it. All of you who create. You can just release it. You don’t always need big rollouts, spending thirty years in blood and sweat. Then you end up tying yourselves up, which breeds fear. Then it takes thirty years for something to come out. That’s why we never got Detox. They overdo it. I did it too, caring about every detail, but now I know that sometimes a track is just good. It doesn’t always have to be innovative and push forward. Sometimes you just want to wear a white t-shirt.”¹⁶ (Editor’s note: This is a loose quotation of Tyler, summarizing the point of his statement.)

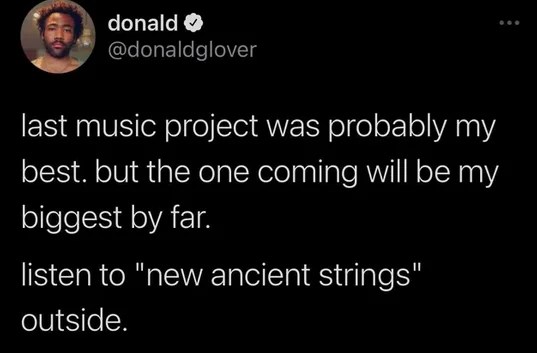

I find it interesting how minimalist rollouts did no harm to Kendrick’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers and GNX. Representatives of New Criticism would explain this by saying that his works function without us needing to add anything from the outside. On the other hand, the mysterious project 3.15.20 by Childish Gambino went completely unnoticed at the time of its release.

“There’s the project 3.15.20 that I put it out. Nobody ever heard it. People didn’t even know I put it out.” ¹⁷

“It’s not easy to put that album into context. And I feel I kind of learned that. It is just hard with streaming. If it were just a [physical]¹⁸ album, there would be certain boundaries, but it’s streaming. The time codes [as track titles]¹⁹ aren’t how people listen to music anymore. I think that album works better as vinyl.”²⁰

Once again, we can find support in New Criticism. What Childish Gambino intended and what he envisioned in 3.15.20 did not automatically appear in the audience’s reception. It’s amusing that it was precisely Tyler who once criticized Gambino’s mysterious method of releasing 3.15.20. ²¹ Opinions change, and all of Tyler’s musical releases reflect these changes; therefore, I see nothing hypocritical in the fact that today he would likely defend Gambino’s initiative to release an album without any context.

I think it is appropriate to subject Walton’s proposal—that the author of a work is master of the correct way in which it will be received—to critical scrutiny. Tyler himself is aware of the limits of his ability to oversee the reception of his own creations.

“The world says, ‘I like this.’ ‘Like Him’ is the biggest track on Chromakopia. ‘Sticky’ is second. They’re right next to each other. I thought ‘Darling, I’ and ‘Sticky’ would be the biggest. ‘Like Him’ and ‘Sticky’ are multi-platinum. You just never know. On this album, I thought it would be ‘Ring, Ring, Ring’ and ‘Sugar On My Tongue.’ So far it looks that way, but we can’t know how it’ll be in a month and a half.”²²

The absence of control over what and how the audience will take away is even more evident when we hear that Tyler was unsure whether to include “Like Him” on Chromakopia at all.

“‘Like Him’ almost didn’t make it onto the album. Daniel [Caesar] ²³ looked at me and asked if I’d lost my mind. He told me to put it on the album. I realized he’s the person who recorded, mixed, mastered, and released the track ‘Vince Van Gogh.’ He has genius in him. He knows what he’s talking about.”²⁴

I would like to support the significant active role of the listener and perceiver with the theory of the American media theorist John Fiske.

“A whole range of films, recordings, and other products that, by people’s decisions, became costly failures (the most famous example being Edsel), demonstrates that people’s interests are not identical to those of the industry. If a commodity is to form part of popular culture, it must reflect people’s interests. We cannot describe popular culture as a process of consumption but as a culture—that is, an active process of creating and circulating meanings and pleasures within a social system…” ²⁵

Whether DON’T TAP THE GLASS will actually be enjoyed in motion and at full volume through large speakers depends on the listener themselves, who in this piece may just as easily actively discover entirely different personal values and ways of experiencing it. We can further recognize our freedom of experience and continue to move away from the author’s intentions and personality together with Roland Barthes.

“To give a text an Author means to impose a safeguard on it, to provide it with a final label, to close off writing. This concept fits very well with criticism that aims primarily to discover the Author in a work (or his hypostasis: society, history, spirit, freedom): once the Author is found, the text is ‘explained,’ and criticism has won.”²⁶

“In the multiplicity of writing, everything is actually to be unraveled and nothing to be deciphered. Structure can be followed, ‘unraveled’ (as they say of a running thread in a stocking in all its variations and sequences), yet it is bottomless. We can traverse the space of writing, but not reveal it; writing continuously offers meaning, but always only for it to immediately dissolve: writing performs a systematic liberation from meaning.”²⁷

“…the birth of the reader must be paid for by the death of the Author.”²⁸

Before concluding, I will briefly digress and ask: When New Blue Sun by André 3000 was nominated for Album of the Year at the 2024 Grammy Awards, was it truly evaluated for his artistry on wind instruments, or rather for his rap merits and impressive shift in creative focus? I am a huge admirer of André 3000; his creative pivot deserves all the respect, as it represents almost a paradigmatic work according to Rick Rubin’s Creative Act ²⁹ and the historical practice of dilettantism, which was regarded across the ages as an intellectual ideal of the elite. Yet, within the framework of this essay, I want to mention New Blue Sun as an invitation to reflect on whether it was truly the inherent qualities of the work itself that garnered so much attention, or whether the frame and context emerging around the author’s persona played a decisive role.

This essay is not a verdict that we must uncompromisingly abandon the author’s persona along with the context it provides. It is a participation in a long-standing debate. My experience of DON’T TAP THE GLASS became richer once I included the framework in which the album was created. Even the misunderstanding regarding lyrical emptiness disappeared. The phase of DON’T TAP THE GLASS will be as valuable a diary entry for Tyler, The Creator’s work as all his previous musical albums. It will forever stand as a record of a period when he wanted to move and invited us to join him. Whether we join the dance at full volume or take away from the work our own values and meanings will remain our free choice, beyond the reach of any manifestos or instructions.

Title illustration by Marttina

- [1] BEARDSLEY, Monroe C., WIMSATT William Kurtz: Intencionální klam. In: Onufer, Petr (ed.): Před potopou: kapitoly z americké literární kritiky 1930-1970, str. 151.

- [2] BEARDSLEY, Monroe C., WIMSATT William Kurtz: Intencionální klam. In: Onufer, Petr (ed.): Před potopou: kapitoly z americké literární kritiky 1930-1970, str. 151-152.

- [3] BEARDSLEY, Monroe C., WIMSATT William Kurtz: Intencionální klam. In: Onufer, Petr (ed.): Před potopou: kapitoly z americké literární kritiky 1930-1970, str. 156.

- [4] SAINTE-BEUVE, Charles-Augustin: „O kritické metodě“. In: týž, Podobizny a eseje. Praha: Odeon, 1969, str. 215.

- [5] Clipse: The ‘Let God Sort Em Out’ Interview | Rap Life, 01:16.

- [6] NIETZSCHE, Friedrich. Tak pravil Zarathustra. Vyšehrad, 2020, str. 126.

- [7] Tyler, The Creator: The DON’T TAP THE GLASS Interview | Zane Lowe Interview, 13:03.

- [8] WALTON, Kendall. Kategorie umění. In: ZUSKA, Vlastimil. Umění, krása, šeredno. 2004. Karolinum, 2004, str. 51.

- [9] WALTON, Kendall. Kategorie umění. In: ZUSKA, Vlastimil. Umění, krása, šeredno. 2004. Karolinum, 2004, str. 66.

- [10] WALTON, Kendall. Kategorie umění. In: ZUSKA, Vlastimil. Umění, krása, šeredno. 2004. Karolinum, 2004, str. 69.

- [11] WALTON, Kendall. Kategorie umění. In: ZUSKA, Vlastimil. Umění, krása, šeredno. 2004. Karolinum, 2004, str. 71.

- [12] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 27:00.

- [13] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 27:27.

- [14] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 1:03:03.

- [15] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 1:06:11.

- [16] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 1:00:31.

- [17] Gilga Radio – Episode 1,1:05:08.

- [18] Vložená poznámka do citátu

- [19] Vložená poznámka do citátu

- [20] Gilga Radio – Episode 1, 1:06:50.

- [21] WILLIAMS, Aaron. Tyler The Creator Loves Donald Glover’s ‘3.15.20’ But Hates The Way He Released It.

- [22] Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him, 57:24.

- [23] Vložená poznámka do citátu

- [24] Daniel Caesar & Tyler, the Creator Talk Friendship in Hilarious Interview | Billboard Cover, 15:50.

- [25] FISKE, John. Komodity a kultura. Online. Revue pro média č.1: Média a populární kultura, str. 1.

- [26] BARTHES, Roland: Smrt autora, in Aluze 10, č. 3, 2006, str. 77.

- [27] BARTHES, Roland: Smrt autora, in Aluze 10, č. 3, 2006, str. 77.

- [28] BARTHES, Roland: Smrt autora, in Aluze 10, č. 3, 2006, str. 77.

- [29] RUBIN, Rick. Tvůrčí akt: Způsob bytí ve světě. Aurora, 2023.

References

- BARTHES, Roland: Smrt autora, in Aluze 10, č. 3, 2006.

- BEARDSLEY, Monroe C., WIMSATT William Kurtz: Intencionální klam. In: Onufer, Petr (ed.): Před potopou: kapitoly z americké literární kritiky 1930-1970. Praha: Revolver Revue, 2010.

- NIETZSCHE, Friedrich. Tak pravil Zarathustra. Vyšehrad, 2020. ISBN 978-80-7601-109-0.

- RUBIN, Rick. Tvůrčí akt: Způsob bytí ve světě. Aurora, 2023. ISBN 978-80-8250-100-4.

- SAINTE-BEUVE, Charles-Augustin: „O kritické metodě“. In: týž, Podobizny a eseje. Praha: Odeon, 1969.

- WALTON, Kendall. Kategorie umění. In: ZUSKA, Vlastimil. Umění, krása, šeredno. 2004. Karolinum, 2004, s. 49-76. ISBN 80-246-0540-6

Web sources

- Clipse: The ‘Let God Sort Em Out’ Interview | Rap Life. In: Youtube [online]. 10.7.2025 [cit. 19.08.2025]. Dostupné z: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q23MQ94OJOw&t=3747s

- Daniel Caesar & Tyler, the Creator Talk Friendship in Hilarious Interview | Billboard Cover. In: Youtube [online]. 24. 7. 2025 [cit. 19.08.2025]. Dostupné z: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Z0Hc98I_BE&t=972s

- FISKE, John. Komodity a kultura. Online. Revue pro média č.1: Média a populární kultura. 2001. Dostupné z: https://rpm.fss.muni.cz/Revue/Revue01/preklad_fiske_01.htm. [cit. 2025-08-19].

- Gilga Radio – Episode 1. In: Youtube [online]. 8.5.2025 [cit. 19.08.2025]. Dostupné z: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUytxKVZ_rI&t=4567s

- Tyler, The Creator talks being nervous rapping with The Clipse and what LA means to him. In: Youtube [online]. 29.7.2025 [cit. 19.08.2025]. Dostupné z: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQFQ-3d2J-8&t=4057s

- Tyler, The Creator: The DON’T TAP THE GLASS Interview | Zane Lowe Interview. In: Youtube [online]. 7.8.2025 [cit. 19.08.2025]. Dostupné z: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xnj1zy1Cz5Q&t=784s